In 1972, the Monte Real Yacht Club organized the most important ocean regatta of those held until then in terms of the number of participants. 48 ships from 35 clubs from 11 countries with some 500 people on board left Bermuda on June 29 for Baiona with the aim of replicating the navigation that 479 years earlier, in 1493, had been carried out by La Pinta de Pinzón on its return to Spain. to announce a new continent, which would be called America. Known as the Discovery Regatta, Discovery Race or BB (Bermuda-Baiona), some of the most prominent American businessmen of the time participated in it, people such as the press magnate Beaver Brook; and a single Spaniard, Alfredo Lagos from Vigo, who with his presence helped to silence the comments of the press that branded the Spanish sailors as not very adventurous for not being part of the crossing. Today, 50 years after that competition, the archives of the organizers (MRCYB, New York Yacht Club, Royal Bermuda Yacht Club and The Cruising Club of America) barely keep a few documents and photographs of its celebration but everyone remembers very well what was: one of the most important regattas in the history of navigation, with the highest number of participants to date.

It is a report by Rosana Calvo,

communication manager of the MRCYB

“Battered the ship by the storms but not the hearts” . This is how the historical documents (and also the commemorative monolith erected in the fishing village of Baiona) describe the arrival, on March 1, 1493, of the Pinta caravel of Martín Alonso Pinzón to the Galician port with one of the most important news in history of mankind: the discovery of America.

479 years after that chapter, the Monte Real Club de Yates, one of the most outstanding clubs in Spain at that time, promoted the most important regatta of the time in his honor, a competition of more than 3,200 miles in which the participants would replicate the journey of the caravel across the Atlantic.

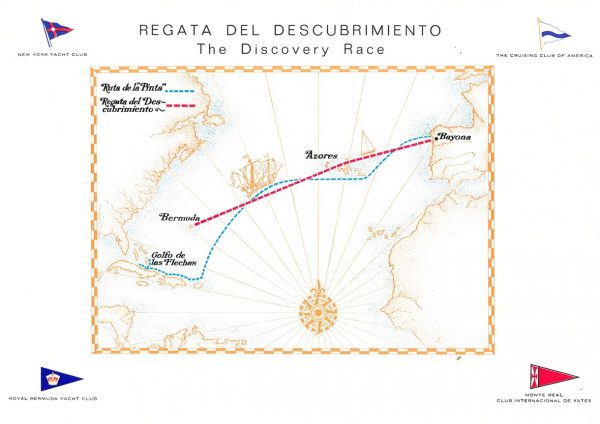

They called it, as it could not be otherwise, the Discovery Race, Discovery Race or BB (for Bermudas-Baiona), and in its organization they collaborated hand in hand with Monte Real, the New York Yacht Club, the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club and The Cruising Club of America.

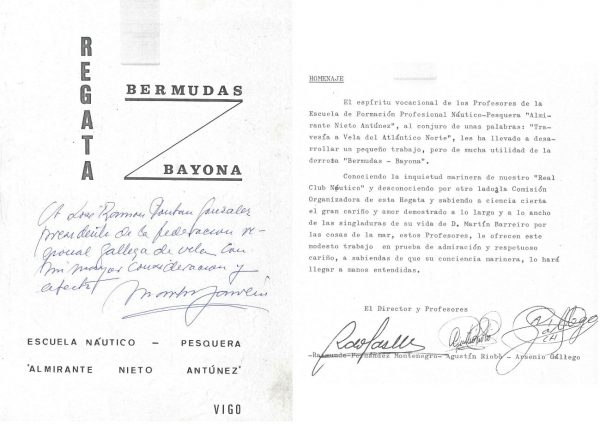

It is difficult to attribute a paternity to the initial idea of the regatta. Many speak of Fernando Solano, who advanced in the sponsorship negotiations with Fraga and the organization with the clubs involved. Other names that appear in the records as main promoters are those of Richard B. Nye (chairman of the regatta committee), Hugh CE Masters (commodore and chairman of the committee of the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club), and José María de Gamboa (chairman of the committee Spanish of the regatta).

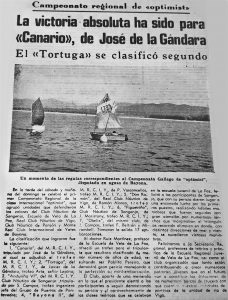

They also promoted the celebration of the competition and the former mayor of Vigo, José Ramón Fontán, was part of the Spanish committee; one of the historical figures of sailing in Galicia, recently deceased, Fernando Massó; the patriarch of the Gándara, José de la Gándara; Jose Maria Padro; the Vigo industrialist Alfredo Lagos; the president of Monte Real until 1971, Alfredo Romero (who would be succeeded by Carlos Zulueta between 71 and 73); and the commodore of the Baionese club until 1971, Manuel Varela.

A regatta simmering for a decade

It was a regatta that was simmering for nothing more and nothing less than 10 years, since 1962, when people began to talk about its celebration; until 1972 when it was finally played. In between, the project was formally presented to the then Spanish Minister of Information and Tourism, Manuel Fraga Iribarne, who would end up approving its patronage; it was exposed to the American clubs that would finally be involved in the event together with the Monte Real (the New York Yacht Club and the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club); and in 1969 the first official meeting with the Spanish Sailing Federation was held.

In 1970, two years before its celebration, there was already a propaganda brochure for the regatta, for which, initially, the name “The Race of Discovery for La Pinta Trophy TransAtlantic” was proposed, which would eventually be simplified to ” The Discovery Race” . In it all the details of the competition were explained. It would be a test of about 3,000 miles of route that would be carried out with the only condition that a minimum of 15 boats register for it.

The most important and massive regatta of the time

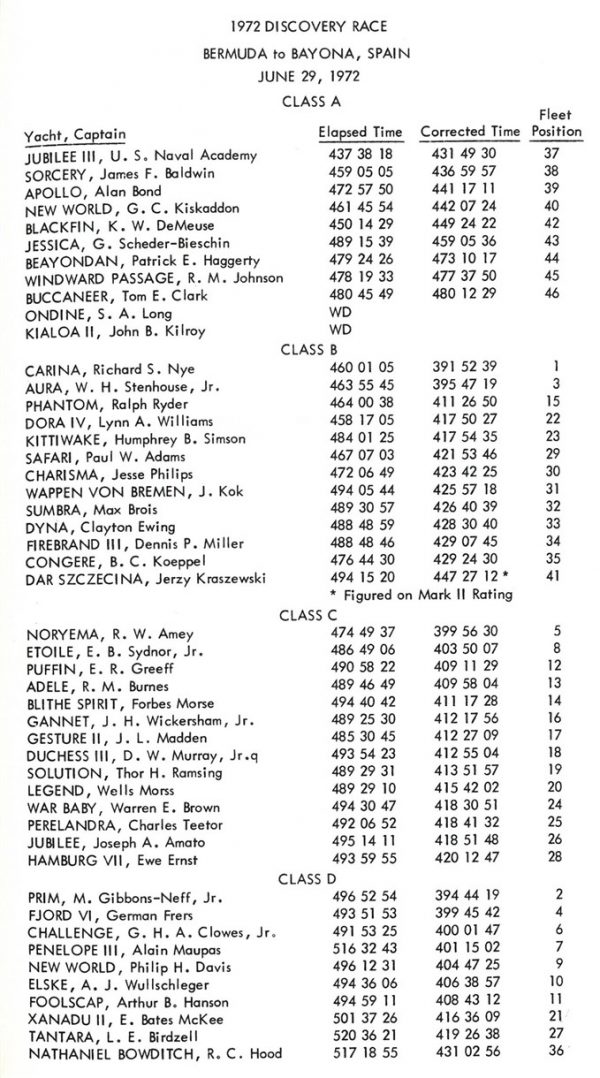

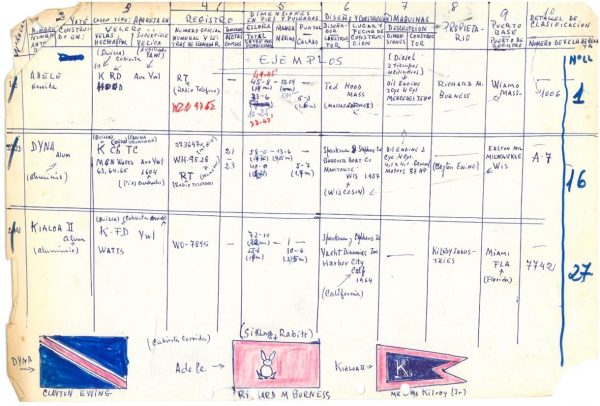

Participation forecasts, not very high at the beginning, ended up exceeding all expectations and the Discovery Regatta finally had a total of 57 registered (of which 48 ended up starting), becoming the most important regatta held to date. date, with the highest number of participants of all time.

Among the boats entered, the majority between 40 and 60 feet (between 12 and 18 meters), the smallest was the French Penélope III, owned by Alain Maupas Trinidad, with a length of 40 feet / 12 meters; and Patrick E. Haggerty’s Beayondan, at 81 feet long / 24.6 meters, the largest.

As a curiosity, it should be noted that there were sailboats, such as the 43-foot / 13-meter New World, by North American Phillip Davies, which was built specifically for the regatta; and that in the test, which was attended by important American businessmen, the second Baron Beaverbrook, son of the well-known British press magnate William Maxwell Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook), founder of newspapers such as the Daily Express or the Sunday Express, also participated.

Alfredo Lagos, the only Spaniard on board

Among all those registered there was only one Spaniard: the renowned industrialist from Vigo and experienced sailor Alfredo Lagos, son of the founder and director for more than 50 years of Astilleros Lagos, one of the most prestigious companies worldwide for its work in the construction and restoration of classic wooden boats.

With his presence as a crew member aboard the Dora, Lagos helped to silence the comments of the press of the time, which branded the Spanish sailors as “not very adventurous” for not wanting to participate in the regatta (or for not daring, as they even came say some, for “risk and fear” ).

A regatta marked by the weather

The Discovery Regatta was set to start on June 28, 1972 from the historic Gulf of Las Flechas (named for the arrows launched by members of the Ciguayos tribe against the Spanish in what is considered the first incident against the European invasion in America), just as the Pinta had done on January 16, 1493, but for technical reasons they ended up setting sail a day later from the port of Hamilton.

Ahead, the 500 participants aboard 48 boats from 35 clubs from 11 countries, had a journey of 3,200 nautical miles / 5,926 kilometers (according to the official route), although everyone expected it to be more (about 4,000 / 7,408 km) per the winds and currents that would influence their journey. And the truth is that the weather ended up affecting, and a lot, the test.

En route from New York to Bermuda for the start of the race, some boats were hit by a typhoon, forcing four of them to abandon the competition and delaying the start for a day so that the rest could make some repairs. Later, once the journey had begun, the poor state of the sea made navigation difficult. And a few days later, more problems. There were several days of calm that would cause a considerable delay in the completion of the test.

The Discovery Regatta was the first international competition that forced the crews to give their situation every day, something that, in addition to generating security, facilitated the tasks of the regatta committee to control the fleet and the work of the press of the time to narrate the evolution of the test. But what initially worked smoothly soon went awry. The participants stopped complying with the requirement because they also provided information to their rivals and the test was carried out practically in its entirety, with few exceptions, without real and continuous monitoring of the sailboats.

It is known, from the data provided in the early days, that the sailboats took three different navigation routes. Some opted for the shortest and most direct route, others went north in search of more favorable winds and the rest sailed south. But when they really began to distance themselves from each other, the calm ones arrived and the crews were unable to establish important advantages, practically all remaining grouped in a platoon while the lack of wind lasted.

Four days into the test, the radiograms sent to New York announced Tom Clark’s Buccaneer (New Zealand) in the lead. On the island of Flores (Azores), the only record set on the regatta’s transatlantic route (850 miles / 1,574 km from the finish line), Charisma captained by Jessie Phillips (Dayton, Ohio) was first, followed by Carina of Richard S. Nye and the Jubilee III, of the United States Naval Academy, captained by Commander Howard Randall.

In mid-July, a Canadair CL-215 seaplane from the Search and Rescue Service arrived in Vigo to carry out its first exploration operation within a radius of action of some 200 miles / 370 km. Baiona, but the results were negative. On a second outing he managed to locate one of the participants, the Solution, 6 miles / 11 km from A Guarda, but the crew had lowered sails and headed for the port of Vigo, implying that they had withdrawn from the competition. Somewhat further away, a group of fishing boats sighted, off the Berlengas Islands (north of Lisbon), the bulk of the crews.

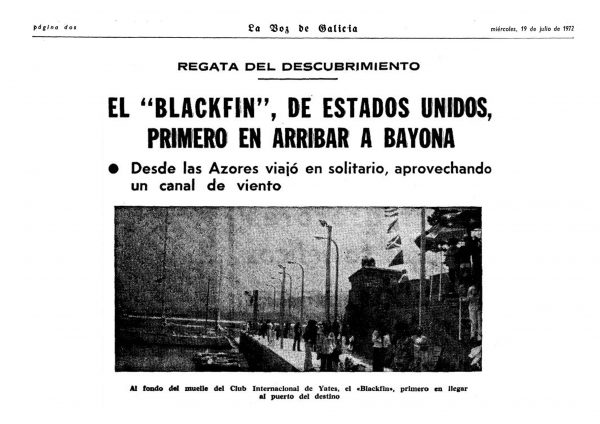

The Blackfin, first. The Carina, winner.

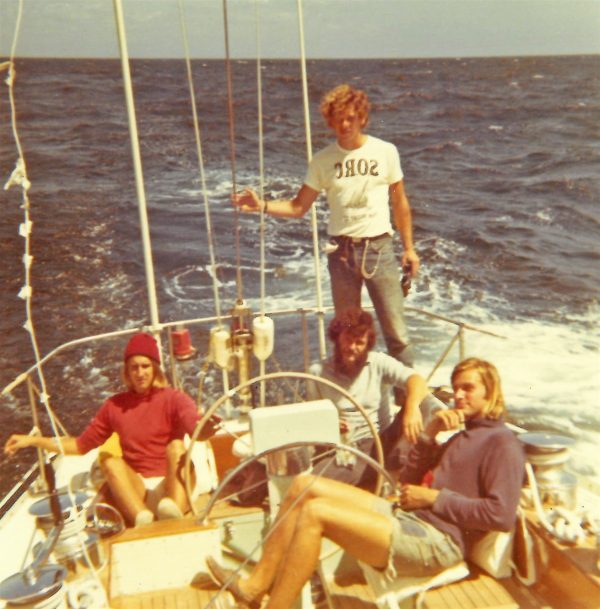

Although the Discovery Regatta boats were scheduled to arrive in Baiona on July 14, it was not until July 18, at 12:15 when the Blackfin (US-flagged, sail number 8910, 73 feet long / 22 , 25m and 16 adventurers on board), led by Kenneth W. DeMeuse, crossed the finish line, an imaginary line that left the Prince’s Tower (where some of the snipe boys and cruisers like the Fontán brothers stood guard , Quico Arbones, Humberto Cervera and others) at 180º magnetic. With the exception of the calm one that was found at the exit of Bermuda, the sailboat sailed practically the rest of the route without problems, taking advantage of a wind channel. He did it alone, investing a total of 453 hours, and upon arrival, the 15 crew members threw their captain overboard to celebrate the victory.

DeMeuse, exhausted and with his hair messed up from the dip, called his country to say that he had arrived, ordered a cubalibre with lots of ice and attended to the media. He commented that the regatta “was not as difficult as it was long”, he explained that it became complicated at times when crossing with very strong winds or with no wind, but that both the crew and the boat ( “which is good and fast” , he assured) they worked very well.

Hours later, around eight in the afternoon, the second ship, the Jubilee III, of the United States Naval Academy, a 22.25-meter sailboat and the number 1800 on its sails, arrived on the old continent. It was manned by 17 people, skippered by Commander Howard Randall and, as had happened to the Blackfin, it also played against the basses of Carallones.

On July 21, three days after the first boats had crossed the finish line, there were still sailboats to finish the journey and among them were some of those that could be proclaimed absolute winners (due to the time compensation system that would be applied for level out the differences between large and small boats). The last yacht to arrive, the Tanatara, did so on the 22nd, and it was then that the final classification of the competition was revealed.

The winner of the 1972 Bermuda-Bayonne Discovery Regatta was the Class B Carina, skippered by Richard “Dick” S. Nye, in 391 hours, 52 minutes and 39 seconds. They were followed in the table by Prim (Gibbons Neff Jr.), from class B, with 344 hours, 44 minutes, 19 seconds; and the Aura (Wallace Stenhouse), also in class B, with 395 hours, 27 minutes, 19 seconds. The Blackfin, the first to arrive in the waters of Baiona on the 18th, was finally in 42nd place in the general classification.

Richard S. Nye (1904-1988) found his love of the sea late and knew little of sailing when he bought the Carina in 1945, but he soon began sailing and ended up competing in long-distance regattas, which became in his passion. He participated in a large number of them and came to win 7 transatlantic races, including the Bermuda Baiona, in which he won with the first of his three Carinas.

The skipper attributed (he always did) the success in this regatta and many others he won to the good work of his crew, made up of his son Richard B. Nye, as first officer, and other members of his family and close friends.

Those who knew him say that he did not sail to win, but because he was truly passionate about the sea. To posterity he passed his phrase: “Okay, boys, you can let the ship sink!” , pronounced after finishing the Fasnet Race of 1957 in a Carina badly damaged by the hard competition.

His victory in the Discovery Regatta had a great worldwide echo and in the final broadcast of the event, everyone agreed on the great success that the event had brought.

The Discovery Regatta, much more than a regatta

In a meeting with journalists, the president of the Monte Real Yacht Club and vice president of the Spanish committee in charge of organizing the arrival, Carlos Zulueta, highlighted the four most significant aspects of the regatta: economic, tourist, historical and sporting.

The competition, sponsored by the Ministry of Information and Tourism (understanding that it would serve to promote tourism at the highest level and offer the Rías Gallegas a high-ranking international sporting competition), had become the one with the greatest participation up to that time and accommodation reservations made in Baiona had repercussions on hoteliers with a figure that exceeded one million pesetas. Restaurants, taxi drivers and other businesses also made cash during the Americans’ stay in the fishing village.

Alfredo Lagos, the only Spaniard in the competition, complained, once it was over, about the little attention the national press and television had devoted to it. blamed “a hidden force that tries to minimize everything in Galicia, which takes us back to times before the Catholic Monarchs. You already know -Lagos said in a special report for the magazine Pesca y Náutica- that when a drop of water falls in Estaca de Bares, although we have an ideal day in Baiona, the phrase is “It rains in Galicia”. For many Galicia is very far away, the roads are very bad, there are many cows and the women carry the load on their heads. Those who only think this, it is much better not to come”.

The truth is that everyone welcomed the crews with open arms and the sailors were able to enjoy the culture, landscape and gastronomy of Galicia for several days. In Vigo, in the gardens of the Pazo Quiñones de León, a dinner was organized for them, enlivened by folk groups. In Baiona, another dinner and a big dance.

They also attended the famous Mougás gigs and ate grilled sardines, empanada and octopus in a mountain refuge. And at the end, many of them took part in a cruise along the Galician estuaries from Baiona to Fisterra, sailing through the most touristic points of coastal Galicia and taking a bus trip to Santiago de Compostela.

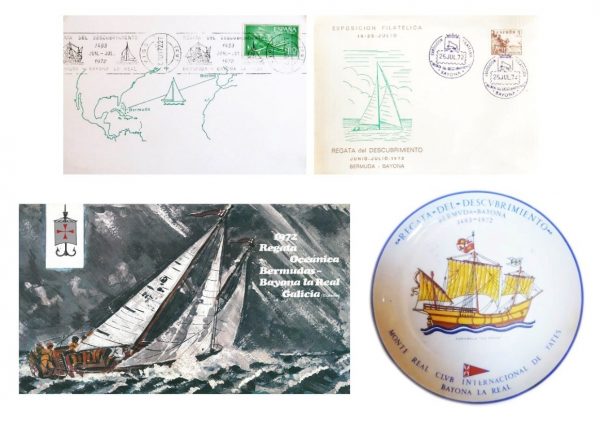

Postmarks, brochures, commemorative plates, flags… recall one of the most important regattas in the history of navigation. A regatta that served for several clubs on both sides of the Atlantic to strengthen ties and promote what ended up being the most massive nautical competition organized to date.

Half a century after its celebration, at the Monte Real Club de Yates de Baiona, the seed of the competition, they remember it as something historic, as one of those events worthy of having gone down in the history of world sailing along with other milestones of the club as the challenge to the America’s Sailing Cup.

And the same what “The noble town of Baiona, an ancient Celtic hedgehog, had the honor of being the first to announce, to the astonishment of the world, the miracle of the discovery of the Americas”, the Monte Real Club de Yates had the honor of being the first to organize a regatta in his honor, the most important of the time and one of those that will always remain in the memory.

It is a report by Rosana Calvo,

communication manager of the MRCYB